Essays: Ted Fendt on “Moses and Aaron”

From the Success of Misuse Back Into the Desert

An essay by Ted Fendt from the Blu-ray/DVD of Moses and Aaron

Moses and Aaron stand side-by-side in the amphitheater of Alba Fucens. Aaron has performed two miracles to convince the people that the new God exists and to follow them into the desert. For the first time in the film, the camera suddenly tracks forward, framing Aaron in a low-angle close up.

As he becomes closer, larger, he tells the people that in the desert they will not want for nourishment: “The Almighty changes sand into fruit, fruit into gold, gold into delight, delight into spirit.” Danièle Huillet: “No one has ever written anything more materialist or less puritanical.”[1] In a film where the primary role of panning and tracking shots is to define spatial and character relations, this shot at the end of Act I stands out for the way it seems designed to emphasize Aaron’s words. Huillet again: “That’s the key to Aaron for me. That’s why we get closer to him at that moment.”[2]

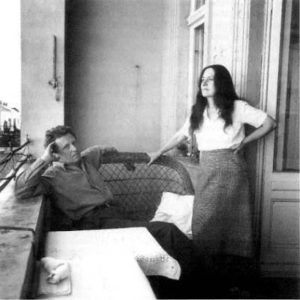

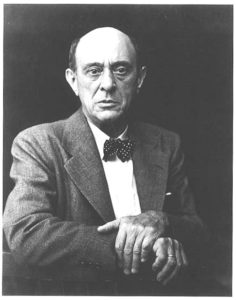

In 1975, talking about the project which had occupied them on and off since 1958, Straub and Huillet said they had gradually become more and more fascinated by Aaron. Staging Schoenberg’s opera with its unfinished third act for the first time, Straub and Huillet’s film contains two endings: one where Aaron rules the day, another where Moses does. At the end of Act II, Aaron has convinced the people to follow him through the desert to the “land that flows with milk and honey;” Moses sinks down in defeat at his inability to convey his message of an “unimaginable” God: “O Word, thou Word, that I lack.” This is where Arnold Schoenberg’s score ends and where all previous productions of the opera had ended. But Schoenberg drafted a libretto for a third act that he—perhaps tellingly—never managed to put to music.

After an abrupt ellipsis and location change, Moses is standing over Aaron, now lying on the ground, bound hand and foot. Moses again has the final word, but it is of a far different tone than before: “…always, when you leave the absence of desire of the desert and your gifts have led you to the highest height, always will you be hurled down again from the success of misuse back into the desert.”

The conclusions of Acts II and III are at odds with each other. Straub and Huillet’s brilliance—and a fundamental aspect of their method of adaptation—is to allow the contradictions of their source texts to remain not reconciled. Through their presentational, analytic method, they make the contradictions more palpable.

The film faithfully stages the opera: “everything is said, sung, or performed—musically and dramatically, with few exceptions—as indicated by Schoenberg.”[3] A Straub-Huillet adaptation contains, nevertheless, small, select additions that re-orient the original work in its new form as a film.

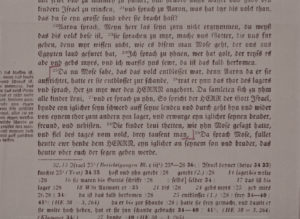

The first image of the film is a passage of Exodus from Luther’s translation of the Bible read aloud by Huillet. It describes Moses’ reaction upon returning from Mount Sinai and seeing the people worshipping the Golden Calf. He commands the sons of Levi to grab their swords, go through their camp and kill brothers, sons, and neighbors: “[They] did as Moses had said to them, and there fell that day of the people three thousand men.” Chronologically, this slaughter takes place in the gap between Acts II and III. This quote looks ahead to elided, later events and emphasizes the political nature of Moses’ mission.

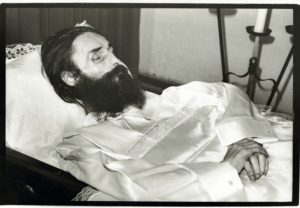

A second addition: following the opening credits, a one-second dedication to Holger Meins, the German filmmaker, Red Army Faction militant, and friend of the Straubs. During the editing of the film, Straub and Huillet saw a photo of his emaciated corpse in an Italian newspaper. He had died during a hunger strike while imprisoned, and his photo, they said, reminded them of the concentration camps. As Cyril Neyrat argues, this dedication implicitly connects Moses and Aaron to the Straubs’ previous film, Introduction to Arnold Schoenberg’s Accompaniment to a Cinematographic Scene, and its ruminations on states and the catastrophes of industrial capitalism.[4]

All the more powerful for their brevity and unexpectedness, these small additions draw attention to the central conflict with which Schoenberg was grappling: whether the Israelites should establish a state or forever wander in the desert. Straub: “Aaron’s idea is a crossing to arrive in a country. Moses’ idea is crossing the desert endlessly. It’s the idea of nomadism, very simply.”[5]

Like so many characters in Straub-Huillet’s films, they are dreamers of a new world. Aaron’s idea that fascinated the Straubs is that of a “promised land” flowing with “milk and honey.” This is the idea that seduces the people at the end of Act I. To the contrary, Moses’ idea is that of forever wandering, never settling down. In the final lines of the film, before a quick cut to the end credits, Moses tells Aaron: “in the desert you are insuperable and will reach the goal: united with God.”

Schoenberg was unable to write music for this act of his opera. The impossibility of resolving the opera’s central issue or committing fully to one side could have been the cause. Works whose internal contradictions resisted them, resisted easy solutions, fascinated Straub and Huillet. Unresolved tensions abound in their work, gradually extending into a great array of diverse and contrasting accents, colors, shadow and light, and costumes. This is what is radical in Straub and Huillet’s cinema and why their films are so rejuvenating, why they make us see anew.

—-

[1] “Conversation avec J.-M. Straub et D. Huillet,” Cahiers du cinéma, no. 258-259, July-August 1975, 16.=

[2] Ibid. 16-17.

[3] Benoît Turquety, Danièle Huillet et Jean-Marie Straub: “Objectivistes” en cinéma (Laussane: L’Age d’Homme, 2009), 145. My translation. The best book written on Straub and Huillet and one of the greatest books on cinema.

[4] Likewise, the inclusion in Fortini/Cani of music from Act II connects the subsequent film to the others in a loose trilogy considering Zionism.

[5] Cahiers du cinéma, ibid.

Ted Fendt is a filmmaker, translator, and projectionist based in New York. He is the editor of “Jean-Marie Straub & Danièle Huillet” (Austrian Film Museum / FilmmuseumSynemaPublikationen, 2016). He has translated English subtitles for several Straub-Huillet films, including Cézanne and Kommunisten. Other translations have appeared in Writings, Cinema Scope, and Robert Bresson (Revised). His films, including Short Stay and Broken Specs, have been shown internationally in film festivals and cinematheques.

—-

This essay is included with our Blu-ray and DVD of Moses and Aaron, available here.